A disaggregated credit theory of home prices: explaining Canada's real estate bubble

Over the last 20 years, real estate prices across Canada have gone up by over 236%, but during that time the average weekly wage only increased by 75%. It's obvious that Canada is facing a real estate bubble.

For a while now experts have attempted to explain the cause of the bubble. From foreign money to supply issues to low interest rates, several theories have been put forward. However, many of these explanations - especially those considering interest rates - have fallen short, either because there's a lack of evidence or because they are based on questionable assumptions. What's more, the recent resumption in home price growth, despite the implementation of government policy designed to solve the issue, casts doubt on the degree to which public officials understand the underlying cause of the real estate bubble.

To fill this gap, we use an explanation of home prices that is linked to mortgage credit issued by commercial banks. In this article I present evidence that not only helps us better understand Canada's real estate bubble, but more importantly, offers some insight on how to solve it.

Explanations for the real estate bubble

Specialists often attribute the rapid price rises in Canada's real estate markets to speculative activity and foreign investment. They also point at increasingly lower interest rates on mortgages, which are thought to have made home ownership more appealing to consumers. More recently, housing supply issues have been blamed. The Bank of Canada blames "froth" when discussing the housing market.

Over the last couple of years we've had a chance to see how these theories perform through various government programs aimed at increasing housing affordability across Canada. In 2016, a foreign buyers tax was introduced in the province of British Columbia to contain speculative investments and laundered funds from going into the housing market. Meanwhile, in Ontario, the province setup the Fair Housing Plan, which put into place a number of things such as rent control, a non-resident speculation tax, a vacancy tax, a 5-year plan to build rental apartments, among other things. Most importantly, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) introduced and then bolstered the B-20 Guidelines by levying stress-tests on uninsured mortgage products (a huge chunk of the mortgage market). This stress-test qualifies mortgage applicants at interest rates that are higher than those posted by the market. The finance ministry also introduced programs that provide interest and principal-free loans to first-time home buyers that can be used as a down-payment.

Recent data shows that national home prices are increasing once again and have broken previous all-time highs. Toronto's market is growing again, with prices increasing by 4.48% on a year-over-year basis in December 2019. Even markets in Western Canada like Vancouver and Calgary are starting to stabilize despite weak economic conditions. Canada's home price-to-rent ratio remains higher than that of the US prior to the housing crash of 2007-2008. Meanwhile, UBS's Global Real Estate Bubble Index still ranks Toronto and Vancouver within the top 5 cities in the world at risk for a housing bubble crisis. Many Canadian households continue to spend over half of their after tax income on housing. It is important to note that the initiatives introduced since 2016 remain in place.

The problem with conventional approaches

One reason why government policies have been ineffective at containing asset price inflation in the real estate market is because they rely on conventional assumptions that do not sufficiently account for the underlying cause of home price growth in Canada. In terms of speculation and foreign cash, according to Statistics Canada, the majority of residential property owners in Canada are individuals and residents of Canada (95.5% in Ontario, 92.7% in British Columbia, and 92.1% in Nova Scotia). In terms of supply, over the last 10 years, Canada's unabsorbed new construction inventory has been growing. This at least partially eliminates speculation, foreign cash, and supply problems as sufficient probable causes of Canada's real estate bubble. If speculation or foreign cash was a problem, we would see much more ownership concentrated in the hands of corporations or at least non-residents, for example. If supply was a problem, we would see low unabsorbed new construction inventory levels across the board.

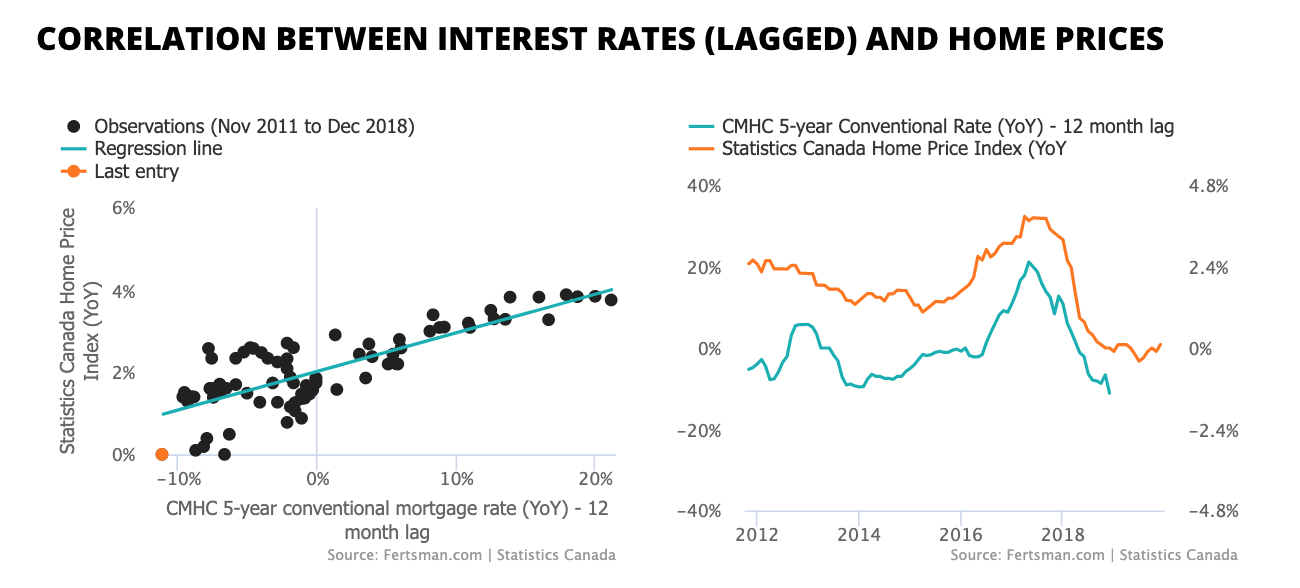

In terms of interest rates, they are not correlated with home prices the way most think. I have put together two charts above that capture the relationship between interest rates and home prices. I use data from Statistics Canada (see the charts above) for the period between November 2011 and December 2018. I have also lagged interest rates by 12 months to better "fit" the data and simulate potential real world effects.

Recall that some believe low interest rates are the cause of high home prices, which implies an inverse correlation. By this logic, home prices can be understood as a function of mortgage interest rates , and we should be able to see positive home price growth when interest rate growth is negative. However, based on the charts above, this theory does not hold. In the scatter plot chart there is a strong positive relationship between interest rate growth and home price growth. This is easily observed in the line chart above. (I have also observed the data by not lagging interest rates, but the correlation is zero. In other words, there is no identifiable relationship between interest rates and home prices when rates are not lagged by 6+ months.) According to the data, lower interest rates are associated with lower home price growth and vice-versa. In fact, a 20% increase in interest rates is linked to as much as 4% growth in home prices. This goes contrary to conventional thinking.

So, why are we drawing conclusions about home prices by looking at interest rates?

The causal role of residential mortgage credit

We consider home prices to be a function of mortgage credit quantities in dollar terms, rather than the cost of the mortgages per se. Mortgage statistics can tell us how much people are spending on real estate because the overwhelming majority or real estate transactions involve a mortgage. And a mortgage is simply credit that is created by licensed commercial banks and sold at interest for the explicit purpose of purchasing a home via a deposit (money). It's a favourable measure of spending on real estate.

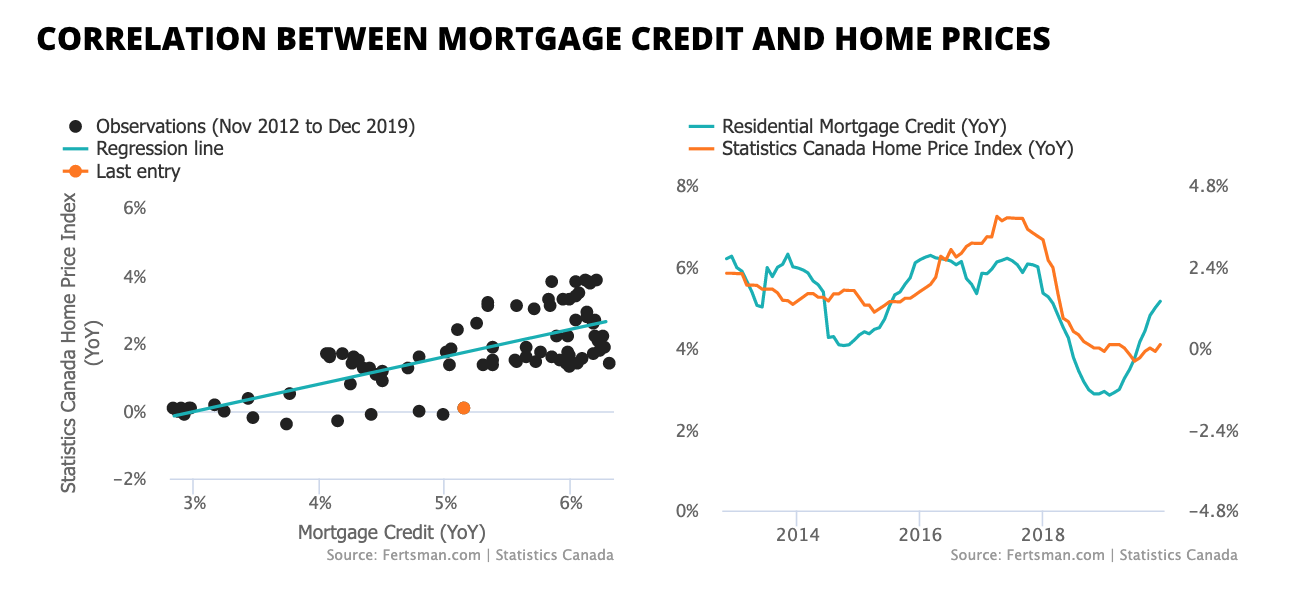

Above, you will find two charts that capture the relationship between residential mortgage credit quantities (in Canadian dollars) and home prices (as measured by Statistics Canada's home price index). Because the majority of deposits attained from a mortgage are spent on real estate transactions, we can safely assume that residential mortgage credit has an effect on the residential real estate market (the Statistics Canada home price index is a measure of prices in this market).

Recall that we conceive of home prices as a function of mortgage quantities. On the charts we should be able to see a a positive increase in home price growth when there is a positive increase in residential mortgage credit growth. In other words, more mortgages in dollar terms should result in higher home prices in dollar terms, as well as the other way around. As you can see on the charts above, the relationship holds. In the scatter plot chart there is a strong positive relationship between residential mortgage credit growth and growth in home prices. This is also observable in the line chart. Moreover, there is no lag in the data! On average, a 6% increase in mortgage credit on a year-over-year basis should result in over 2% growth in Statistics Canada's home price index on a year-over-year basis.

We can now begin to better understand why home prices are breaking highs in December; mortgage credit grew by over 5% (rates on mortgages are still dropping though!). Taxes and other government policies had no overall effect in calming home price inflation since they didn't address mortgage credit growth (if anything, Trudeau's first-time home buyer program likely contributed to higher mortgage growth since it lowered a barrier to entry). Accounting for the role of bank-issued mortgage credit is crucial. We now have evidence that growth in mortgages leads to predictable consequences on the growth of home prices. The interest rate on the mortgage matters to the extent that it prevents or enables someone to get a mortgage, but if we want to clearly understand prices we need to look at credit quantities.

The causal role of residential mortgage credit

So, what should governments do? The information above can be used to craft clever policies that reduce the risks that have built-up in the real estate market. The immediate solution would be to curb commercial bank mortgage originations. A limit of mortgage credit growth would decrease the flow of newly created deposits (money) from going into the real estate market. This would have the effect of lessening the pool of money that is inflating home prices. From there, banks can focus on lending into other sectors of the economy, like the business sector in order to produce good jobs with high wages (the impact of bank-issued commercial loans on wages is similar to the effect of mortgages on real estate). Those wages can then be used to fund home purchases, rather than using bank credit.

Existing deposits (wages) are far less inflationary than credit (newly created deposits). Governments need not be weary of other sources of money that are going toward home purchases since the majority of home transactions are facilitated via a mortgage. Outstanding residential mortgage credit comes in at over $1.22 trillion Canadian dollars as of December 2019. To put this into perspective, there were only $2.07 trillion in deposits (money sitting in chequing accounts) that same month. Over half of all money in existence in Canada's banking system was created through real estate transactions. Policies that target the source of this money creation - bank mortgages - will be very effective.

Ultimately, it would be up to elected officials to decide how strict the limits on mortgage originations should be. But many challenges exist to any such approach. First, mortgages compose over 40% of total commercial bank assets (loans); nearly half of the banking industry earns fees and interest from mortgage activity. What's more, other financial products like home equity line of credits (HELOCs) tend to rely on ever increasing home prices . Secondly, somewhere between 10% to 20% of Canada's GDP is composed of transactions affected by mortgage activity. To make matters worse, over 50% of mortgages are insured by the federal government. So, it's unlikely that governments and banks are incentivized to embrace any policies that limit credit expansion, at least not until it's too late. This is the world we've created.

Cover image by: Markus Spiske via Unsplash

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Enjoyed this article and want to support our work, but are using an ad blocker? Consider disabling your ad blocker for this website and/or tip a few satoshi to the address below. Your support is greatly appreciated.